Establishing the Creative Hook

After struggling through audience analysis in Chapter 1 – the most fundamental constraint of creating entertainment – it’s normal for creative folks to feel a little deflated. We picture ourselves as ‘creative’, and more often than not don’t want to think of the process as being so clinical. We reach for those flashes of insight that set our ideas apart from others.

Unfortunately, most creative people have a haphazard, unpredictably intuitive approach. We know that as professionals, we are expected to meet deadlines. Yet we also know that it isn’t possible to force ourselves to have a creative thought.

Go ahead and try. Right now. Say something creative.

It isn’t easy is it? When most people are taken unaware by a question like that, a deer-in-the-headlights look appears in their eyes. They stammer for a moment and, for most of them, the first thing out of their mouths is either something incredibly weird like “let’s go into the kitchen, grab some lint from under the fridge, and make a sandwich out of it,” or they ask a question like “Creative how? Like something funny? Inspirational? Poetic?”

The first example, something so bizarre that it probably isn’t a phrase that has ever been uttered before, might qualify as ‘creative’ to some people, but true creativity has to be more than stringing together a collection of words that are only interesting because that they haven’t been arranged in that order before. If that constituted creativity, then we could just pin some dictionary pages to a wall and hand some darts to a roomful of monkeys, and the world would be hailing it as a creative breakthrough.

The second reaction, asking questions in order to narrow down the field of possibilities, is more useful and instructive. It gets at the heart of the creative process. Let’s take a moment to understand that.

Many years ago, I found a useful definition on the creativelearning.com website. It defined the creative process as “the forming of associative elements into new combinations which is in some way useful. The more mutually remote the elements of the new combination, the more creative the idea is.”

Although that’s an incredibly useful definition, you might have to read it over a couple of times to get the gist of it. Try focusing on the phrases “in some way useful,” “forming of associative elements” and “mutually remote.” These three phrases are the keys, so let’s take a look at them individually.

In some way useful – This is the reason that the lint sandwich doesn’t qualify as creative. Simply jamming two ideas together that have no connectivity between them is random – difference for the sake of difference. We are left with something that can’t exceed the sum of its parts. It is different, that’s true, but it’s also pretty useless. What can you do with a lint sandwich as a concept? Nothing. Combining two concepts together when they have no chance of enhancing each other is pointless.

Forming associative elements – This part of the definition is the central core of the creative process. Associative elements are two or more ideas that are somehow related or connected. For instance, we commonly associate the color green with money. For Americans, at least, that’s obvious because paper money uses green ink. Creative people, rather than looking at the common connections between ideas, have the ability to find the unusual connections. If robust and interesting enough, these connections are what enable the useful element of the definition.

Mutually remote – This part of the definition is a refinement of the associative element component. When the two elements are too closely connected, it leaves no room to explore the nature of their connection. Try reading that last bit again: the nature of their connection. The way in which two ideas are connected is really the thing that we identify as creative. That unusual connection is what engages the audience’s brain, and makes them speculate and wonder. So, when the two ideas are known to already be connected, like vampires being predators, the result is uninteresting. It’s a cliché. The best examples of mutually remote ideas cause observers to see both ideas in a new light, and spawns further ideas from that starting point. In other words, the connection, that entity which forms the bridge between the two ideas, is the important part. This is what enables the mutually remote ideas to exceed the value of their sum. Individually, each idea can be simple and mundane, but when combined together, they create new possibilities.

This discussion allows us to modify our definition for the creative process, which will introduce some useful nuance.

The creative process is the associative effort by which a distant connection between two seemingly disparate ideas can be found. The nature of this connection must be unusual and cause the observer to see both ideas in a new and usual way, thus, engaging the observer’s own creativity.

Note the final phrase: thus, engaging the observer’s own creativity. This is an extremely important part of our definition. With enough experience, we eventually realize that we can tell that an idea is creative when the audience sees ways to use it that we didn’t.

In other words, a truly creative idea makes the audience think, and even feel creative themselves.

Examples of Remote Associations

Let’s say we associate dragons with treasure hordes. That’s common enough that it won’t raise any eyebrows. But now, let’s focus on the word ‘horde.’ Maybe we associate that with greed. Even with that tiny step, we’ve created some distance from the original notion of a dragon. Even so, a greedy dragon is still dull, so we need to keep at it. Create some more distance.

Greedy people are stingy with their money. Personally, I find this behavior to be obsessive compulsive. When we apply this to the dragon, creating a creature that is obsessive compulsive, we are moving into more interesting territory. Obsessive compulsive people demonstrate a bunch of interesting behavior traits, so let’s tag our dragon with a few possibilities:

- Obsessive washing or cleanliness, or a dragon neat freak

- Excessive doubt or concern that if everything isn’t done perfectly, something awful will happen, or Eeyore the dragon

- Excessive counting or arranging, those who are obsessed with order and symmetry, maybe Sheldon Cooper as a dragon

- Fear of losing control, or a dragon control freak

- A germaphobic dragon might be the reason they are so reclusive

- Excessive focus on religious or moral ideas would give us a cult leader dragon whose followers think it is a god

- Extreme superstitions regarding numbers, colors, symbols or arrangements, which makes me smile to think of the dragon that is afraid of black cats

- Ritualized behavior might cause our dragon to be almost comically predictable, which is the only thing that gives the hapless St. George any chance at all of beating it

- Extreme nervousness or anxiety. Can you imagine a dragon with the personality of Dobby the house elf?

Applying one or more of these to our dragon will result in an atypical creature – something that doesn’t conform to the stereotypical image of a dragon. Yet the plausibility of it is confirmed through our logical chain of reasoning. Obsessive compulsive behavior would make sense for a dragon, given the behavior they demonstrate in common dragon lore.

Our logic chain might look like this:

Dragon –> Collects horde –> Obsessive compulsiveness –> A nervous, germophobic, religious martinet that collects rare items in pairs, but only on Sundays

Clearly, this isn’t the standard kind of dragon we would find in high fantasy, and as such, we have a basis to dream up interesting stories, situations, and interactions. In other words, our remote association is useful.

Typically, when we think of dragons, we envision huge, red, fire belching, knight eating, damsel capturing, flying reptiles. They’re predatory, cunning, and evil. Can you say ‘cliché?’ This boring idea has been done to death thousands of times already. Been there, done that. Yawn. Creative? NOT! There’s almost nothing new we can contribute to that kind of dragon.

On the other hand, if we start thinking about our obsessive-compulsive dragon, a wealth of possibilities open up. This kind of dragon can actually have an unusual personality. If she is obsessive compulsive, perhaps it has some of the related personality disorders and neuroses.

These neuroses should make logical sense for its situation, but again, that just opens up more possibilities. Perhaps our dragon is paranoid. After all, there are a zillion St George wannabes looking to slay her. She’s probably a chronic worrier. If it’s a two headed dragon, wouldn’t it develop a split personality? What if our dragon has hyper-acute senses? Maybe she believes the distant voices she hears are actually the voice of God speaking into her mind.

You get the idea. You can sail into uncharted waters pretty quickly if you start with a concept that uses remote associations.

Over the years, students in my class on game design have used this process to provide some fun results.

Vampires –> Drink blood –> Health risks (from blood transmitted diseases) –> Vampire hypochondriac

Vampires –> Blood is food –> Blood lust (compulsion to eat) –> Eating disorder –> Morbidly obese vampire

Ghost –> Dead person –> Grim Reaper –> People fear death –> Ghost fugitive, running from the grim reaper

And even if we don’t provide the chain of logic that connects the starting and ending points, the results themselves are usually self-explanatory. It isn’t hard to provide the chain of logic that connects the following:

Alien travel agent

Incompetent alien that gives away dangerous technology

Demon in an anger management program

Therapist for AI programs who are struggling to find themselves

Shark hitman

Demon corporation that deals in souls as a commodity

Double agent with a split personality

Mary Kay vampire selling eternal youth

Emo unicorn

Alien rock star

Feminist succubus

Autistic robot

Serial killer priest

Dragon trapped in the friend zone with the captured princess who is awaiting her knight

Note how in each instance above, the two opposing ideas aren’t terribly original. We all have a stereotypical image of an alien, just like we know what a travel agent is. But it’s not the individual opposing ideas that provide the energy for creativity. The real keys to creativity are the implications that result from combining them. This is the filter through which we should measure our efforts. If combining two ideas has implications that we haven’t seen before, then chances are it’s creative. (And even if you want to quibble about the definition of creativity, it’s at least going to be entertaining, which is all that matters.)

From this point on, we’ll refer to this short sentence that establishes the remote association as the creative hook. It is a fundamental necessity of character design, and when used properly, a huge percentage of the design feeds off of this short, powerful phrase.

As a side note, you should soon realize that the broader your knowledge base, the easier it will be to come up with creative ideas. For instance, in the dragon examples above, we needed to have had enough exposure to dragons to know that they commonly have treasure hordes. We also needed to have some limited exposure to psychology in order to connect greed to obsession, and then later to various neuroses or obsessive-compulsive behaviors. Sometimes you will have to do some research about the base subject in order to get some ideas, but in general, the more you read, watch movies, play games, etc, the easier it will be to get the ball rolling. Creative people are usually voracious readers and highly methodical researchers.

Mind Mapping

Although seeing results is all well and good, it doesn’t help us if we don’t have a reliable way of achieving them. We need a structured, reproduceable method for generating ideas at will, because our tyrannical bosses always have the unreasonable expectation that we can be creative on a schedule. (And they can have that expectation because they don’t have to do it.)

Relax. Take a few deep breaths. It’s not impossible. In fact, creativity isn’t some mystical gift from the gods. It’s a skill, and like any skill, it can be learned, trained, and improved. All you need are some techniques, and happily, that’s one of the main points of this post.

The first method we’ll take a look at is a technique commonly known as a Mind Map. The term Mind Map was first coined in 1974, but the idea has literally been around for centuries. It began with some historical guy named Porphyry of Tyros in the 3rd century, when he used graphical representations to depict Aristotle’s Categories.

Since then, it has evolved an avalanche of functionality, used by educators, engineers, psychologists, scientists, etc. as a method to model systems, solve problems, and record information. For our purposes, it boils down to a tool that facilitates problem solving.

And that’s all creativity is: a specialized kind of problem solving.

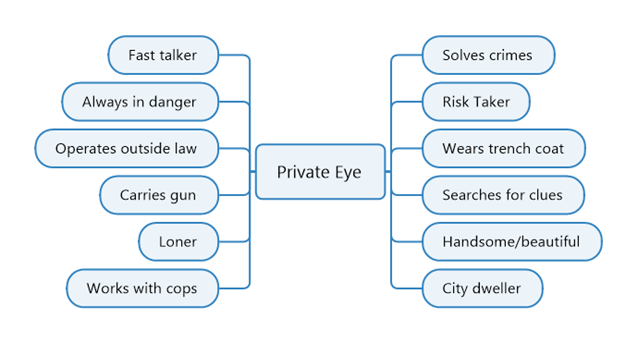

So how does it work? Let’s start by building an example. Say we want to brainstorm a new Private Investigator character. Write the words ‘Private Eye’ in the center of the page, and then create a field of little bubbles around it, with each one showing all the stereotypes we can recall that are associated with private eyes.

This represents the fairly chaotic jumble of stuff that pops into people’s heads when they think about private investigators. None of it is the slightest bit interesting, except for one thing.

This represents the fairly chaotic jumble of stuff that pops into people’s heads when they think about private investigators. None of it is the slightest bit interesting, except for one thing.

Each bubble brings with it more associations.

Recall that creativity is rooted in the ability to associate – to connect different pieces of information. And also recall that to be creative, most things have to form connections that are remote from each other. In other words, we need to extend our mind map out to the next level.

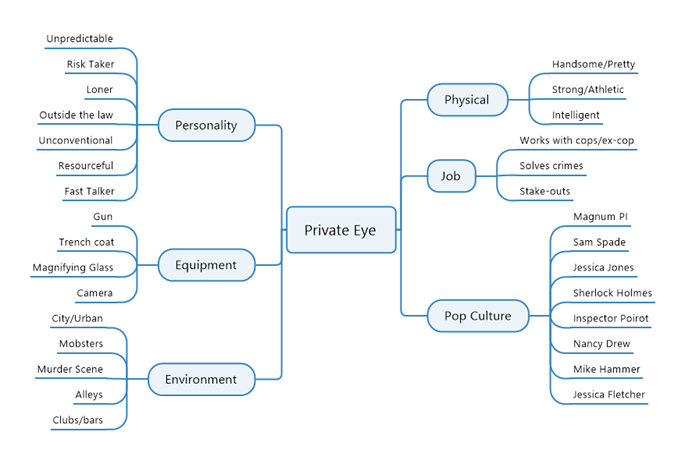

But before we do that, let’s look at our current map a little more closely. Notice how our stereotype observations each seem to belong to a kind of category. Fast Talking, Risk Taking, and Loner are all personality traits. Carries a gun and wears a trench coat are both common equipment for them.

Before we move on, it’s useful to regroup our ideas. We’ll find that when we do this, it actually shows us where we could add in even more stereotypical information. And the more things we bring to the table to associate with, the more opportunities we have for unearthing something interesting.

By this point, we’re still in the land of stereotypes, but by sorting our observations into categories, we’ve been able to provide more data to associate with. New opportunities are going to start coming into focus.

By this point, we’re still in the land of stereotypes, but by sorting our observations into categories, we’ve been able to provide more data to associate with. New opportunities are going to start coming into focus.

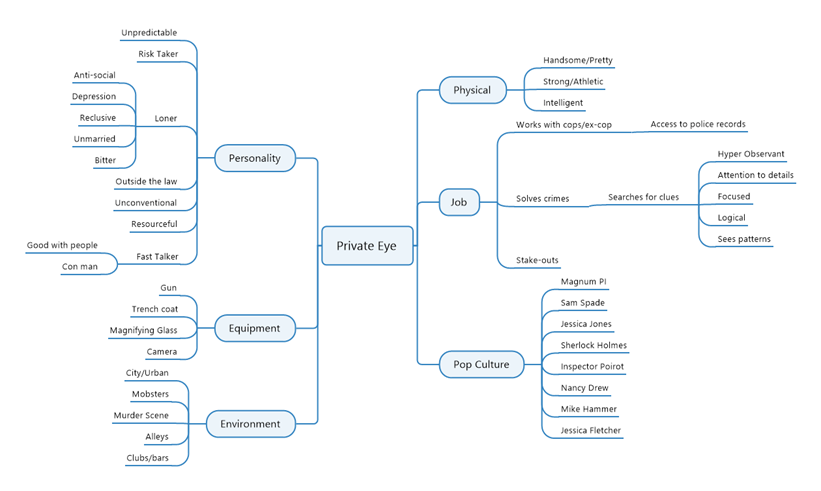

To get there, we need to look at the edges of the mind map and ask ourselves things like “what are the implications of this?” and “what does this word or concept make me think of?” That will allow us to expand it further.

At this point, if you let your mind wander over the mind maps and look for patterns around the edges, certain words and concepts will jump out at you. Viewing above, we find, anti-social, reclusive, hyper observant, unpredictable, and sees patterns.

At this point, if you let your mind wander over the mind maps and look for patterns around the edges, certain words and concepts will jump out at you. Viewing above, we find, anti-social, reclusive, hyper observant, unpredictable, and sees patterns.

Ignoring private detectives for a moment, allow this collection of words to swarm around in your head. What other sorts of people might these words apply to? Perhaps an accountant, computer programmer, doctor, or an author? Unsurprisingly, some of these occupations pop up in movies that feature amateur detectives. Jessica Fletcher is a writer. Dr. House is, for all intents and purposes, a detective who solves medical mysteries.

Or we may look at the words around the edges of our mind map and see types of people instead of occupations. The same words that jumped out at us before, “anti-social, reclusive, hyper observant, unpredictable, and sees patterns” could easily describe someone with OCD, or that obnoxious neighborhood gossip that lives down the street.

Gee, big surprise, we have Adrian Monk, an OCD private detective, and Miss Marple, the neighborhood gossip who is an amateur detective.

If we allow our mind to continue to sift through the edges of our mind map, it might occur to us that those individuals like Sherlock Holmes or Inspector Poirot constantly amaze us with their powers of observation. When Holmes walks into a room and after five seconds says something like “clearly, the killer is well over six feet tall, left handed, and plays golf… on Tuesdays,” it seems impossible. We’re sure he’s just making this stuff up, like some sort of conman or a psychic. (Oh, gee, there’s Shawn Spencer from USA Network’s Psych). Or the word anti-social, for me, leads to ASPD and sociopath (Dexter, Prodigal Son).

Or maybe it’s all some elaborate trick, like a stage magician does. Surely, there can’t be a detective who is also a magician? Yeah, actually there is. The 2018 series was called Deception, and featured a Las Vegas illusionist who became the world’s first “consulting illusionist” to work with the FBI.

The fact is, virtually any model for a detective can be found by brute force. Populate a mind map with data that you can associate with the central topic, take it out 4 or 5 levels, and start asking the usual questions like: who else does this remind me of, what does this mean, when does this happen, how does this work, why are they like this, or where do these people come from?

Nothing in the mind maps presented here requires any giant leap of imagination. Nothing requires and particular innate creative ability. It’s all rather formulaic, to be honest. And yet, once you find that unusual connection between two ideas, and you see how it can feed your imagination, you’ve found a creative hook.

Some of the ideas above that we found through straightforward, methodical observation, like Monk and Psych, were hailed as wildly creative when they first hit the airwaves, and won all sorts of awards.

Yet it really isn’t hard to arrive at the same thing.

And I guarantee that if you continue expanding on a mind map like the one above, interesting connections will appear. There are plenty of undiscovered models for private detectives. It’s only a matter of taking the time to continuously expand the map, adding more and more ideas to associate with, and exploring the results.

Also note how the mind map is nothing more than a structured approach that allows us to create the chain of logic that was discussed in the previous section. Remember how Vampires –> Blood is food –> Blood lust (compulsion to eat) –> Eating disorder –> Morbidly obese vampire? Can you see how this creative hook can be easily found by using a mind map? We populate the mind map with our associative data, and then just connect the dots from the inner concept to the outer one. Simple.

Why Does This Work?

Personally, I like to take things apart. It’s not enough for someone like me to know that a methodology works. I have to know why. So, when I first started thinking along these lines, ‘why’ was an essential question.

And the answer didn’t take long to discover. This stuff works because the connection between the starting point and the ending point, all the little stereotypical details in the inner areas of the mind map, are strongly connected to both ends. Detectives who are good at solving crimes HAVE to be observant. Not just observant, but hyper observant. And on the other side, doctors, lawyers, people with OCD, and con men are all hyper observant too. But those people come attached to an entirely different set of associations. Their traits and skills are similar to the detective, but for sometimes totally different reasons.

But it’s important that the two ideas are strongly connected by a logical thread. A supermarket cashier would be a poor template to match up with a private detective because the two occupations and personality types have almost nothing in common. But the conman and the detective? Oh yes. They both have to be fast-talking, keen people-watchers, who notice the small details, like the flicker of emotion that flashes across an adversary’s face.

I have to think that a professional poker player would make a good detective, and so would a psychologist. But maybe not an athlete or an opera singer. Of course, maybe a hook could be found if we identified a meaningful association between them. That’s the magic of creativity. It’s all about the way the ideas are connected. It’s about leveraging the commonalities, such that each side of the creative hook contributes to the result in equal measure, resulting in a new and useful spin on an old idea.

The reason anyone can do it is because the mind map itself is just a record of the exact kinds of associations that take place in the mind of a ‘creative person’, often without them even realizing it. Whether because of upbringing or because it’s their natural way of thinking, creative people are able to quickly form the connections between ideas, to see the patterns contained in the big picture and around the edges of the mind map in their heads. For the most part, this shorthand process is totally invisible to them. If asked, they’ll often say the idea ‘popped into their head’ and made sense.

The good news is that this process is reproducible. Anyone can do it. By recording the information in a visual way, where we have access to all of it at a glance, our ability to associate is enhanced. It might not result in a ‘flash of insight’, but if you’re willing to invest a few hours into mapping it all out, the results work out just the same. And the more you practice, the more you’ll develop that internal ability. After enough practice, you’ll learn how to do it automatically and be able to dispense with the mind map if you want.

Tools and Techniques

Software Options

Although it’s easy enough to draw out our mind maps on any handy white board or paper, there are also a variety of software options, both free and professional, that can be handy to help record and present your work. Personally, I use MindJet’s MindManager, but here are a few other options to consider, some free and some professional tools:

- Scapple

- FreeMind

- XMind

- ThinkComposer

- MindMup

- The Brain

- Moo.do

- Lucidchart

- MindMeister

- Visual Understanding Environment (VUE)

- Coggle

- Mind Vector

- Creately

Categorization

Especially in the early stages of creating a mind map, it’s important to categorize. After your first pass at simply noting any random associations that come to mind, take the time to organize. Put each of your associations into umbrella categories, like: personality traits, physical skills and abilities, fictional and cultural examples, occupational tools, symbolism, environments, etc. By doing this, you will clarify the areas where you haven’t paid enough attention yet, and make it easier to see where you are missing possible associations. You’ll often find that behavioral and personality traits yield interesting results.

Nature of Connections

Pay particular attention to the nature of your connections. Allow this to suggest questions, symbols, and avenues for further exploration. Ask constant questions like:

- Why are they like this?

- Who or what else does this?

- Where does this happen?

- What does society think of this, and how does our central topic (or person) react to that or compensate for it?

And don’t limit yourself to asking these questions only about the central topic. Treat each element in the mind map like its only little mini mind map. It is within this kind of exploration that innovations are found. Don’t rush it. It’s often easier if you brainstorm with three or more individuals, and engage in conversation about the different ideas that appear in the mind map cloud.

Concept Mapping

There exists a similar-but-different technique to mind maps. They are called Concept Maps. People often struggle to differentiate between the two because they are similar. Mind maps are primarily used for generating and exploring ideas, brainstorming, and thinking creatively. They revolve around one main focus topic, which expands in a center-out hierarchical structure, where each node represents a specific subtopic.

Conversely, a concept map is used mostly for organizing and visualizing implied knowledge, analyzing complicated problems, and acting on the solutions. They contain larger and more complicated information, and can often be used to show how two different complex topics relate to each other. Thus, concept maps are more factual, as they identify more main concepts and the systemic and conceptual relationships between them. This means that concept maps tend to contain a lot of cross-connections between concepts, rather than being limited to the radial, center-out structure of a mind map.

So why bring this up? Well, firstly because it’s interesting. But secondly, as we will discuss in a subsequent chapter, some designs are more mechanical in nature, as opposed to the subjective ideas that we create with mind maps and creative hooks. For those designs that are more mechanics-centric, a concept map may prove to be a better choice.

Research

Creative people are voracious readers and researchers. By now, you should understand this. The larger the body of knowledge you can feed into a mind map, the more associative scope you have to work with. In other words, with more possible ideas to combine, more opportunities for innovation exist. Thus, a wide-ranging base of knowledge is extremely helpful.

Many creative people have a broad, eclectic set of interests. It surprises eve me how often a knowledge of macroeconomics creates an interesting model for a combat system in a fighting game, or a basic understanding of physics gives me an idea for a medieval fantasy character. Knowledge of different kinds of systems enables a game designer to have ‘models’ from which to draw upon. If they are good at abstracting away the details of the model, removing the specific details such that only the high-level concepts remain, these conceptual models can then be applied to an almost infinite number of other systems.

To put it another way, almost anything can be viewed as a conceptual model and applied as a filter for a wholly different system, providing an unusual vantage point from which new ways of thinking about the original concept can be obtained.

Radar Locking

Avoid the trap of becoming fixated on the first interesting pattern you find in a mind map. Yes, it is possible to come up with an original idea in an initial flash of insight. But often these flashes are based on superficial ideas – we might call them close associations – and surface level associations rarely contain sufficient depth to do anything with them.

If you stumble across an interesting looking example early in your mind mapping process, make a note somewhere, and then explicitly set it aside. When you feel like your mind map is sufficiently populated, try to find multiple creative hooks. Consider each one, seeking to understand how different it is, and how much it inspires further thought. The hook that has the greatest level of these two things is the best candidate for a creative hook.

Opposition

Sometimes, interesting results can be extracted by leaning in the opposite direction from expectations. For example, if we determine in our mind map that a typical soldier is decisive and courageous, then it might be interesting to brainstorm the implications of a soldier who is hesitant and cowardly. Stephen Crane’s Red Badge of Courage springs to mind immediately.

This technique can yield results especially when the quality you are examining is a fundamental necessity of the central topic. In order to explore opposition, it is necessary to discover how our central topic can compensate for the missing key component. Again, exploration is required, but in this instance, it will take on a totally new direction.

Key Takeaways

- Creativity comes from the nature of the connection between two remote associations

- We associate creativity with ideas that are useful and unusual. Simply being different doesn’t accomplish the goal

- Creativity can be brute forced simply by reproducing on paper that process that takes place in the mind of a naturally creative person

- In order to form associations, a solid knowledge of the base subject is essential. Do the research